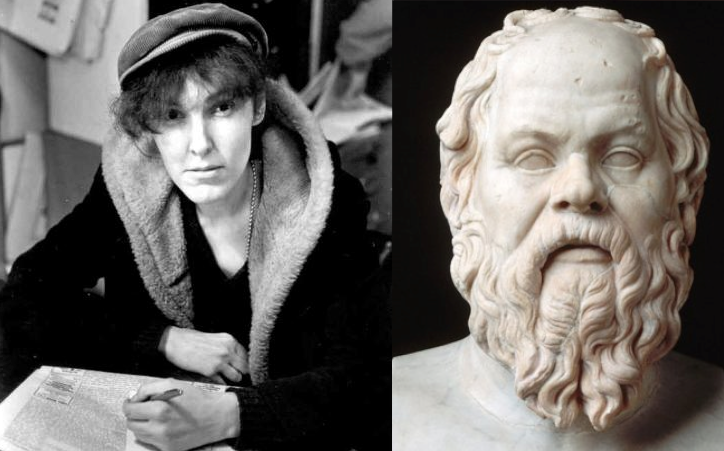

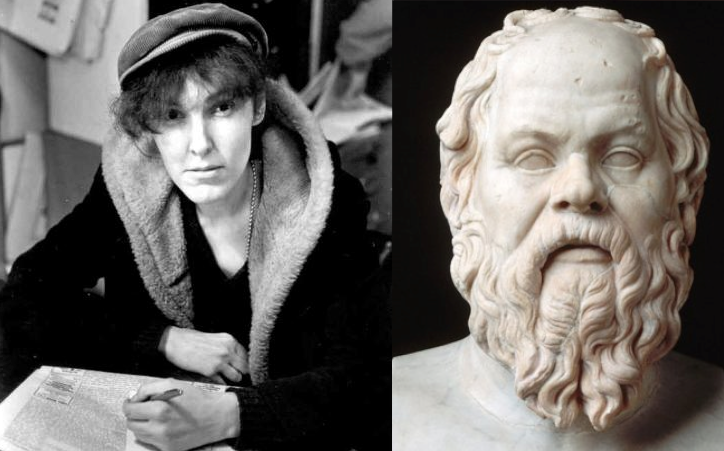

Much has come up lately about the Valerie Solanas’ 1967 radical feminist essay, the SCUM Manifesto. It’s a remarkable read, uncompromising, utopian, and like all good writing, unashamed of being what it is. It is an important piece of writing, and should take its place with the study of literature and ideas. Solanas stands with Pythagoras, Socrates, TS Eliot, and Kant among countless others who put forward theories about the role, origin, and best eventual outcome regarding other members of their societies.

Much has come up lately about the Valerie Solanas’ 1967 radical feminist essay, the SCUM Manifesto. It’s a remarkable read, uncompromising, utopian, and like all good writing, unashamed of being what it is. It is an important piece of writing, and should take its place with the study of literature and ideas. Solanas stands with Pythagoras, Socrates, TS Eliot, and Kant among countless others who put forward theories about the role, origin, and best eventual outcome regarding other members of their societies.

What makes it a good commentary is that it has the feel of many true things in it. But I would ascribe them to what is more commonly called the Patriarchy these days than to the specific genetic condition of maleness, and so for me, that is what makes it not a correct commentary.

I also find the SCUM Manifesto overly utopian, and I am profoundly suspicious of utopias. Like all visions of enforced human improvement, SCUM promulgates a singular vision of human nature, and fails to see more than a binary among womankind. We are not Solanas’ perfect and groovy creatures. If men did not exist, I believe we would have invented them. Ultimately, Solanas’ Manifesto falls to its own assertions. As the superior and only “whole” members of the species, the responsibility for men’s behavior ultimately has to fall on us, like bad tenders of a garden, who let men grow out of control in the first place.

What makes the SCUM Manifesto brilliant isn’t its originality, but its total derivativeness. It echoes countless other manifestos, analyses, philosophical tracts, medical text books, theological arguments, and so on — but from high status men. Many of these men are still regarded with near worship today, like Freud and Kipling. SCUM bears the impression of Charles Dickens, and St Thomas Aquinas. It has more than passing similarities to the ideas of Confucius and the holy texts of the Hindu faith.

It’s just that it’s pointed up the power chain, instead of down. These ideas about inferiority, genetic, intellectual, and spiritual, aren’t new. They’ve been used as justifications to deny meaningful lives to women and low status men by the billions for centuries. I want to point that out again: billions of people for thousands of years.

I’m not going to say Valerie Solanas wasn’t nuts. She clearly was. She shot Andy Warhol. She was also just nuts, there’s no getting around Solanas being not being a very good or well person. I’m happy to leave Solanas to history as unfortunate and somewhat nasty. But on one condition: all the other people who promulgated the same ideas are just as nasty and unreasonable. Solanas goes into a looney bin of horrors. But all those beloved, male, white, or whatever the dominant ethnicity of the place and era, those intellectuals, leaders, and spiritual men of history, even the ones I love, have to go in there too.

Everything they wrote doesn’t have to go in there with them. I still love Kipling and Hemingway, despite the White Man’s Burden and, well, everything Hemingway ever did. I love The Hollow Men, I love the Scholars, I love many things that never pass any variation of the Bechdel Test. But if men’s work, replete in their strange and incidental hatreds get to stay out of the bin of shunned horrors, so does the SCUM Manifesto. Surely any writing that can clearly show that a swath of great thinkers of history were demonstrably insane and cruel belongs among the great writings, even if insane and cruel itself.